Being Lebanese = Speaking Arabic?

This post is written by Amanda Eads, a Sociolinguistics graduate student at NC State University. It is Part 2 of 3 in a series that describes the survey she conducted and her analysis. You can read Part I and Part III.

Studies of identity are complex due to its multi-layered and dynamic social nature. Exploring the relationship of language and identity studies is even more difficult to pursue given the variability in language ideology across cultures and people. Cultural anthropologist Selim Abou (1981) argues race, religion, and language are key factors in determining one’s ethnic identity and that of the three factors, language is the most influential because of its ability to convey the other two factors. Within this context, then, what does this mean for the Arabic language as Lebanese immigrants integrate into American society? Does Arabic survive or does English become the dominant medium in which identity is conveyed? Before delving into my preliminary analysis of the survey, I’d like to share some personal quotes from Lebanese living in North Carolina. Some of these quotes are taken from footage filmed by the Khayrallah Center team for the documentary Cedars in the Pines: The Lebanese in North Carolina (2012). Others are collated from interviews I’ve collected as part of my research. The quotes pertain to language and identity and, as will be quickly evident, opinions and experiences are quite varied. “Not able to speak a word of English comes to America. Comes through Ellis Island. And how he made it, I don’t know but anyway, the clerk asked him his name and so forth and registered him. He says my name is Hanna Makhoul Farhoudi. They knew Hanna was John. Got to Makhoul and they put down M-A-C-K and Farhoudi never got in the ball game at all. So we got named by a clerk at Ellis Island. So that name has hung with us. And then of course, I never have liked the name Mack. It’s certainly not Lebanese but I’ve had it so long I’ve gotten accustomed to it.”

Mitchell Mack, 3rd generation describing his grandfather’s migration experience in 1903 “Unfortunately, I wish I had learned the second language. Um…at the time, I really couldn’t be bothered with it. As a kid I was trying hard to assimilate with the other Anglo-Saxons world that we lived in.” 2nd generation on not learning Arabic while growing up in early the 1930’s “I figured if I learned English coming here, they can learn Arabic if they want to….It’s always good to know a different language, you know you use it around, but I didn’t think it was critical for their upbringing.” 1st generation describing language choices with his children “The bottom line, when I see my kids sitting in front of the TV and they see those Arabic titles coming down the bottom of the news and they can read it, that pays for me. Or what I see is when my kids the first trip went to Lebanon they were able to communicate with their cousins. They did not want to come back to the States- that paid for me. I want them to come back to the States but I’m saying that’s how much, how quick they adopted to the Lebanese community, their grandma and grandpa. They didn’t see it like ‘Whoa, what the heck is that?’ They were all living it here before they went there.” 1st generation describing joy in his children’s Arabic speaking abilities “Speaking Lebanese is crucial to Lebanese identity.” 3rd generation born in 1963, identifies as American-Lebanese, speaks no Lebanese. As I discussed in part 1 of this blog series, the negotiation of Lebanese heritage and new found American-ness manifests itself in differing forms, and this is further evidenced by the comments above. Some immigrants have chosen to maintain Lebanese Arabic while others now view it as a ‘second language.’ But while individual opinions remain diverse, I have found a few trends during the analysis of the survey I conducted with a total of 47 participants.

- Participants consisted of 24 males and 23 females.

- 45 out of 47 have obtained an Associates degree or higher.

- The 2 participants who do not report higher education are still attending or recently graduated from high school.

- 7 participants were born between 1930-1950

- 33 were born between 1951-1985

- 7 were born between 1985-2000.

On the questionnaire, participants were provided several options for identifying their nationality. Here are the totals for each nationality:

- 4 American

- 1 American-Arab

- 9 American-Lebanese

- 10 Lebanese

- 22 Lebanese-American

- 1 Lebanese-Dutch

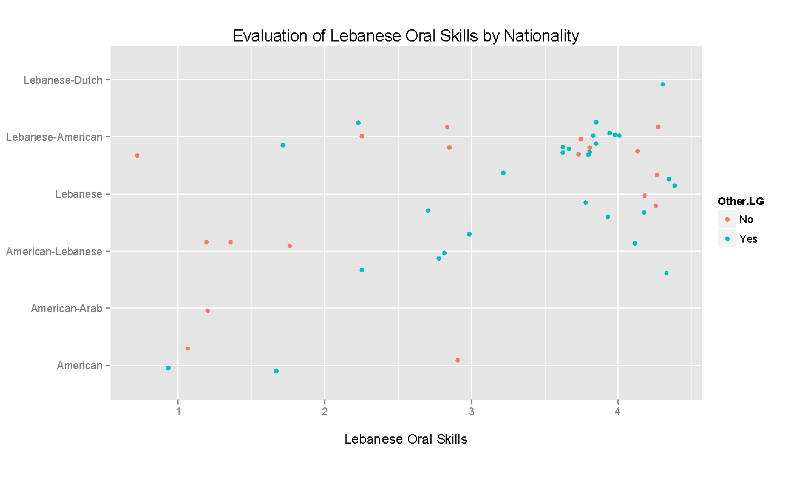

On the questionnaire, participants were asked to evaluate their speaking skills in English and Arabic as well as whether they spoke a third language. The graph below shows the participants’ designated nationality and their self-evaluated ability to speak Lebanese Arabic. In the graph, 1 represents ‘Speaks No Arabic’, 2 ‘Speaks Poorly’, 3 ‘Speaks Well’, and 4 ‘Speaks fluently’. The blue and orange points represent whether the participant speaks a third language.

Linear regression revealed a significant correlation between strong Lebanese Arabic skills and knowledge of a third language. The majority of people who claimed to speak a third language identified French although the participants born between 1985-2000 identified Spanish more often than French. These younger participants who identify Spanish third languages are second and third generation Lebanese born in North Carolina- a state with a large Spanish speaking population [1]. The participants’ report of bilingualism is not surprising given the language history and language education policies in Lebanon. French was used predominantly by Christians particularly the Maronite as an identity marker prior to the French Mandate of 1920. The mandate established France as the governing body of the region thereby broadening the use of French. While the mandate did not require French to be taught in schools, it was common practice for the Lebanese to learn a foreign language usually French or English. In 1990, after the end of the Civil war, the Lebanese government mandated that schools teach Arabic, French, and English (Joseph 2004).

When asked about language mixing, overall the participants (39/47) reported that they find it natural and often mix languages in conversation. Only one participant disapproves of mixing languages and the remaining 7 participants admit to mixing English and Lebanese Arabic, but try to avoid it. Therefore, these participants demonstrate positive language attitudes towards bilingualism and code-switching between languages. The most significant result regarding language use shows a correlation between fluency in Lebanese Arabic and participants who identified their nationality as Lebanese, Lebanese-American, and Lebanese-Dutch. It is important to note that all who identified as Lebanese are first generation immigrants. However, Lebanese-American, Lebanese-Dutch, and American-Lebanese include first generation participants as well. In contrast, this means that those who identify as American, American-Lebanese, and American-Arab do not report strong Lebanese Arabic skills. In fact, there is a clear relationship between strong Lebanese identity with fluency in Lebanese Arabic and strong American identity correlating with ‘Speaking No Arabic’. This is not yet substantiated, but perhaps Arabic language ability influences the hyphenation ranking for some of these participants nationality choices. So does being Lebanese = speaking Arabic? Well, technically, yes. All participants who identified as Lebanese speak Lebanese Arabic fluently. But, does being of Lebanese heritage = speaking Arabic? No. As the personal quotes I included above indicate, the participants’ language abilities and attitudes vary. Language seems to contribute to Lebanese identity, but it isn’t the defining factor. If you are of Lebanese heritage and would like to participate in this study you can find the questionnaire here: http://goo.gl/forms/KLnFfQbmzv.

References

1. According to the PEW research center, 9% of North Carolina’s population is Hispanic and 81% of the Hispanic population speaks a language other than English at home. The home language may or may not be Spanish and the total number does not include non-native Spanish speakers.

Abou, S. (1981). L’identite culturelle, relations interethniques et problemas d’acculturation. Paris: Editions Anthropos.

Joseph, J. (2004). Language and Identity: National, Ethnic, Religious. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Khater, A. & Cullinan, D. (2012). Cedars in the Pines: The Lebanese in North Carolina [Motion Picture]. (Available from North Carolina Language and Life Project, Tompkins Hall, Campus Box 8105, Raleigh, NC 27695).

- Categories: